Visual Perception Art Do You See a Rabbit Blojob

Abstract

This written report examined the effects of ego depletion on cryptic effigy perception. Adults (N = 315) received an ego depletion task and were later on tested on their inhibitory control abilities that were indexed by the Stroop task (Experiment 1) and their ability to perceive both interpretations of cryptic figures that was indexed past reversal (Experiment 2). Ego depletion had a very small result on reducing inhibitory control (Cohen's d = .xv) (Experiment 1). Ego-depleted participants had a tendency to take longer to respond in Stroop trials. In Experiment ii, ego depletion had minor to medium furnishings on the experience of reversal. Ego-depleted viewers tended to accept longer to opposite ambiguous figures (elapsing to start reversal) when naïve of the ambiguity and experienced less reversal both when naïve and informed of the ambivalence. Together, findings suggest that ego depletion has small-scale effects on inhibitory control and pocket-size to medium effects on lesser-upwardly and elevation-down perceptual processes. The depletion of cognitive resources can reduce our visual perceptual feel.

Inquiry over the by 100 years has used ambiguous figures, pictures with more than one estimation, to examine the coaction of bottom-up and top-downwards processing in visual perception (Long & Batterman, 2012; Melcher & Wade, 2006; Ward & Scholl, 2015; Wimmer & Doherty, 2011). Ambiguous figures evoke unlike interpretations while the concrete properties of the stimulus itself remain unchanged. This switching betwixt interpretations is termed "ambiguous figure reversal" (Long & Toppino, 2004). Whilst a plethora of inquiry has demonstrated the coaction of processes allowing reversal, in the electric current research we addressed how the "depletion" of cerebral resources reduces our visual perceptual experience.

Prove from dissimilar fields has demonstrated that inhibitory processes play a key role in the reversal experience. Developmental research has shown that inhibitory ability allows 4- to five-year-former children to feel reversal per se when informed of the ambiguity (Wimmer & Doherty, 2011). Bilingual children who have superior inhibitory control (Carlson & Meltzoff, 2008) are more than likely to reverse ambiguous figures than their monolingual peers (Bialystok & Shapero, 2005; Wimmer & Marx, 2014). In addition to allowing reversal, inhibitory control can also reduce reversal. Adults tin can voluntarily command the perception of one estimation when instructed to hold their first estimation, demonstrating the office of top-down processes in visual perception (Hochberg & Peterson, 1987; Mathes, Strüber, Stadler, & Basar-Eroglu, 2006; Meng & Tong, 2004; Peterson & Gibson, 1991; Slotnik & Yantis, 2005; Suzuki & Peterson, 2000; Van Ee, van Dam, & Brouwer, 2005). However, viewers cannot fully control their reversal rate every bit the teaching to concord one interpretation only leads to a decrease in reversal of between one half and one 3rd over a 3-minute period (Strüber & Stadler, 1999), highlighting the additional role of bottom-upwardly processes in reversal.

The electric current research investigates the specific role of inhibitory processes in reversal and takes an opposite approach. If inhibitory command allows reversal per se, will the depletion of inhibitory processes directly interfere with reversal, thus, reduce information technology? To investigate the issue of inhibitory depletion on reversal, we use an ego-depletion method from social psychology. Ego depletion refers to "a temporary reduction in the self's capacity or willingness to engage in volitional activity, (including controlling the surroundings, controlling the self, making choices, and initiating action) caused by prior exercise of volition" (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998, p. 1253). The underlying principle of ego depletion is that performance on a task requiring self-control will subsequently pb to a subtract in functioning in an unrelated cocky-control chore (Alós-Ferrer, Hügelschäfer, & Li, 2015; Baumeister et al., 1998; Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010). Specifically, participants who cross off some instances of the letter east following complex rules sentry a boring moving-picture show longer when it requires active quitting (pressing a button) than passive quitting (removing the hand from a button; Baumeister et al., 1998). Thus, participants' cocky-control is impaired after monitoring behaviour and overriding a habitual response, such as crossing off all instances of the letter e (Baumeister et al., 1998).

The ego-depletion upshot is demonstrated widely across a range of tasks, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. Ego depletion may reflect a depression-level bottom-up process (Baumeister et al., 1998) or a high-level top-downwards process (Inzlicht, Schmeichel, & Macrae, 2014). The free energy model (Baumeister et al., 1998) purports that cocky-control is a limited resource. In a self-control task, energy is consumed and subsequent task performance requiring self-control will be reduced due to limited energy and its conservation, analogous to a tired muscle (Baumeister, 2014). For example, self-control is linked to claret glucose levels and consuming a glucose drinkable reduces the ego depletion issue (Galliot et al., 2007). In contrast, cocky-control requirements may afterward lead to reduced attention to cues that require command and reduced motivation to exert control (Inzlicht et al., 2014). For case, the ego-depletion event is reduced when participants are motivated to perform a task such every bit thinking that their participation helps in finding Alzheimer'south disease treatments (Muraven & Slessareva 2003). The energy model can business relationship for these findings besides; motivation reduces the ego depletion effect because ego depleted participants can however exert conserved self-control if motivated beforehand (Baumeister, 2014). Overall, information technology is unclear what processes underlie ego depletion per se. All the same, given that ego depletion affects bottom-up processes (Baumeister, 2014) and meridian-downwards processes (Inzlicht et al., 2014), it should reduce ambiguous figure reversal involving both processes.

To exam whether the depletion of inhibitory control leads to reduced reversal, we adapted the well-established ego depletion chore (Baumeister et al., 1998) and measured the effect on inhibitory control, indexed by the Stroop job (Stroop, 1935) (Experiment 1) and reversal (Experiment 2). Specifically, it was examined whether ego depletion affects reversal when beingness naïve of the ambiguity (lesser upwards) versus being informed of both interpretations (acme down). If ego depletion reflects a low-level process (Baumeister et al., 1998), then this should atomic number 82 to reduced reversal under naïve weather condition; whereas if it reflects a high-level process (Inzlicht et al., 2014), then this should reduce reversal under informed conditions.

Experiment i: Establishing ego-depletion effects on inhibitory control

Hither, the furnishings of ego depletion on inhibitory command were examined. Participants were either ego depleted using a well-established ego depletion task (Baumeister et al., 1998) or not depleted and and so subsequently given the Stroop chore, indexing inhibitory control.

Method

Participants

Overall, 214 adults (165 females, One thousand = 22 years, SD = 7 years) recruited via the Plymouth University online participation arrangement participated. They either received course credit or financial reimbursement.

Design

Half of the participants received an ego depletion task (Due north = 113), and the other half an analogous control job (N = 101). After that, all participants received a computerized Stroop task. The experiment lasted around thirty minutes.

Materials and process

Participants in the control condition received a typewritten sheet of newspaper containing technical text (a page from a neuroscience article) and were instructed to cross off all instances of the letter e. Participants in the ego depletion status were additionally told to but cross off an due east if information technology is "not adjacent to another vowel and more one letter away from another vowel" (thus, i would not cross off the due east in pear or vowel) (Baumeister et al., 1998). Eight example words were provided, clarifying the instructions.

After that, all participants received a computerized version of the Stroop task on a standard PC (1920 × 1080 resolution), containing 100 give-and-take-reading, 100 color-naming, and 100 interference trials. Each trial blazon was preceded by ten do trials. Trial type lodge was counterbalanced betwixt participants. Stimuli comprised color words (red, light-green, bluish, yellow) written in cherry-red, green, blue, yellow, or blackness font. Colour words were aligned in a two × two foursquare configuration in the centre of the screen, centred by a fixation cross where the mouse was positioned at the kickoff of each trial. The target stimulus appeared below the square configuration and was displayed until participants gave a response via mouse click, followed past the adjacent trial i,000 ms apart. In discussion-reading trials, the target was a colour give-and-take in black font, and participants clicked on the co-ordinate colour patch (due east.yard., "If the give-and-take BLUE appears, click on the blue colour patch"). In colour-naming trials, the target was a color patch, and participants clicked on the according word (e.grand., "If you run into a BLUE patch, click on the give-and-take blue"). In interference trials, the target was a color word, and participants clicked on the colour the give-and-take is written in (due east.thousand., "If you run into the word Blueish written in scarlet, click on the word red). In interference trials, the colour word was incongruent with the colour the word was written in, in most trials (76 trials), mixed with 24 congruent trials to increase the interference effect.

Results and word

Accurateness on percentage of Stroop trials was at ceiling (ego depleted: Thousand = 98.34; control: Chiliad = 97.89), and therefore no statistical assay was conducted. 8 participants (three ego depleted and five controls) failed all interference trials and were excluded from analyses. The terminal analyses include participants who followed the ego-depletion instructions, that is, both rules (N = 82) and control instructions (North = 95).

We analysed mean response time in the Stroop task using bootstrap resampling to obtain effect sizes. There was barely a response time departure on overall Stroop response time betwixt ego-depleted participants (Chiliad = i,001 ms) and controls (Chiliad = 985 ms), Cohen'south d = .095.

Nevertheless, information technology was of theoretical interest whether ego depletion would reduce inhibitory control rather than all-across-the-board response time. To isolate the inhibitory component, for each participant, the average of their response time in the two command conditions (word reading and colour naming) was subtracted from their hateful response time in interference trials. In this inhibitory mean response time mensurate, ego-depleted participants (K = 233 ms) had a trend to take longer to respond than control participants (M = 207 ms) Cohen's d = 0.15. The same findings were obtained when response time in colour naming was used as comparison against the interference trials (interference latency - colour naming latency); ego depleted (M = 234 ms) versus controls (M = 205 ms), Cohen's d = .18.

Thus, there is a pocket-sized effect of ego depletion reducing inhibitory control. These findings do not support previous inquiry revealing large ego depletion effects on inhibitory control (Johns et al., 2008). Can this small event exist a result of procedural differences of our Stroop version such as responding via mouse click or implementing the traditional blocked trial version every bit opposed to the more recently used detail-by-item version? This seems unlikely as, if anything, the blocked version reveals larger inhibitory control effects than the detail-by-particular version (Ludwig, Borella, Tettamanti, & de Ribaupierre, 2010; Salo, Henik, & Robertson, 2001). Thus, nosotros would have expected to find at to the lowest degree equally large ego depletion furnishings on Stroop performance in a blocked version as in Johns et al.'s (2008) detail-past-particular version. Moreover, the Stroop effect is demonstrated widely across different response modalities (e.thou., oral vs. pressing a keyboard button vs. typing in the give-and-take). At which stage of the task the Stroop effect emerges is subject area to debate (during encoding or response pick), but evidence rules out that the Stroop outcome occurs at response execution (Damian & Freeman 2008; Logan & Zbrodoff, 1998). Therefore, it is unlikely that procedural differences in the Stroop version can explain the differences in the magnitude of the ego depletion effect in our study (d = .15) and in Johns et al. (2008) (d = .76).

Experiment two: The furnishings of ego depletion on ambiguous figure reversal

Having established a pocket-sized reduction of inhibitory control with the current ego depletion task, information technology was examined whether ego depletion reduces reversal (duration to first reversal and number of reversals) when naïve versus informed of ambiguity.

Method

Participants

Overall, 101 adults (69 females) (M = 24 years, SD = 11 years) recruited via the Plymouth Academy online participation arrangement took part and either received course credit or fiscal reimbursement.

Blueprint

Beginning, participants received the same ego depletion (Due north = 51) or control task (Due north = 50) as in Experiment 1, followed by the ambiguous figure (AF) reversal chore.

Materials and process

The ego depletion task was the same equally in Experiment one. The AF reversal task was computerized and ran on a standard PC (1920 × 1080 resolution) in Visual Bones.

Ambiguous figure (AF) reversal task

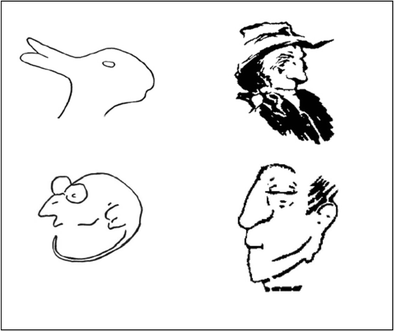

The ambiguous duck/rabbit (xi × 7.5 cm; Jastrow, 1900), man/mouse (8.5 ×7.5 cm, Bugelski & Alampay, 1961), mother/face (9 × ten.five cm; Fisher, 1967), and cowboy/Indian (10 × 11.v cm; Botwinick, 1961) were used (see Fig. i). Participants sat approximately 1 1000 from the screen.

AFs used in Experiment ii (clockwise from meridian-left: duck/rabbit, cowboy/Indian, face/female parent, human/mouse)

Earlier presenting the ambiguous figures, participants received 2 familiarization trials, each lasting 60 seconds. In one trial, the image inverse physically (a horse morphed into a sheep), whereas in the other, no change occurred as the figure was unambiguous (a line cartoon of a daughter). Participants pressed the space bar whenever they idea that the image changed. The purpose of familiarization was to introduce the concept of change without the concept of ambivalence and to control for false positives (people reporting changes without perceiving them) and false negatives (people perceiving changes without reporting them). 2 participants were identified as imitation positives, and their data were removed from farther analyses.

After familiarization, in the naïve phase, participants were presented with the beginning ambiguous figure and uninformed of the ambiguity and alternative interpretations. Participants were asked what they saw (initial interpretation; e.thousand., "a duck"). So, they indicated their perceptual changes via button press over 60 seconds. The plan recorded the dependent variables, (i) when the first reversal occurred (elapsing to first reversal) and (two) how ofttimes reversal occurred (reversal rate). This was repeated with the remaining iii ambiguous figures (human/mouse, cowboy/Indian, face/mother). Ambiguous figures appeared in random society counterbalanced between participants. If participants reversed, then at the end of the naïve phase, they were asked what the alternative perceived interpretation was, ensuring perception of the culling interpretation equally indicated. Alternative labels were accepted every bit long as the participant was able to indicate relevant features of his or her stated inverse interpretation (e.thou., old woman instead of Indian or woman instead of mother with baby or man instead of face).

Then, the informed stage followed the same procedure, except that outset, each figure was disambiguated by calculation disambiguating context drawings for each estimation and each interpretation was labelled (e.g., "This could exist a duck, this could be a rabbit." "You lot volition at present be shown the ambiguous image for lx seconds. Delight press the infinite bar each fourth dimension you lot see the image flip between pictures").

At the cease, participants were asked whether they had seen any ambiguous figure before.

Results and discussion

Information of five outliers (2 standard deviations above the hateful) in the number of reversals experienced in the naïve phase were removed from whatsoever further analysis.

Prior knowledge of ambiguous figures

Depending on the type of ambiguous figure, at that place were considerable differences in whether it had been seen earlier, Friedman examination, χ2(three, 94) = 73.nine, p < .001. Specifically, the duck/rabbit was more than known (all zs > 5.06, ps < .001) (by 45% of participants) than whatever other figure which did not differ (all ps > .05) (Wilcoxon Signed Ranks), except that the cowboy/Indian was more known than the man–mouse (p = .04; face/woman: vii%, cowboy/Indian: 11%, homo/mouse: 4%). Thus, because of loftier familiarity with the duck/rabbit figure to compare naïve and informed phases, this effigy was removed from any farther analyses.

Ambiguous effigy reversal

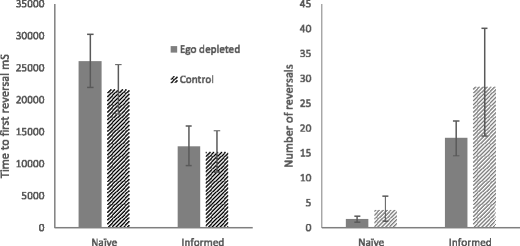

We analysed mean time in seconds to first reversal (duration to first reversal) and mean number of reversals (reversal rate), using bootstrap resampling to obtain conviction intervals on both the mean values and the consequence sizes. Figure two shows the means.

Time to offset reversal and number of reversals for ego-depleted and control participants, when naïve and informed about ambiguous figures. Fault confined are 95% CI

The effect of existence informed near ambiguity is clear, with a marked decrease in fourth dimension to commencement reversal and a large increment in the total number of reversals reported. There is a tendency for ego-depleted participants to have longer to report a reversal and run into fewer in total. Figure three shows the effect size of the differences betwixt groups in each condition.

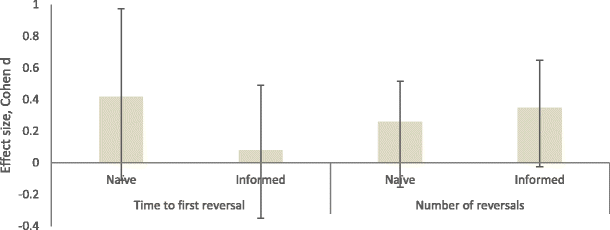

Cohen's d effect size for the departure betwixt ego-depleted and control participants; sign-reversed for number of reversals. Error bars are 95% CI

The estimate of upshot size for time to first reversal is 0.42 in the naïve condition, falling to 0.08 in the informed status. For number of reversals, the issue size increases from 0.26 when naïve to 0.35 when informed (the management of the difference is reverse, as shown in Fig. 2; reversing the sign of Cohen's d makes Fig. 3 clearer. We cannot confidently rule out an effect size of cipher in any condition, due to large individual differences between participants. Still, the pattern seems articulate: while the tendency of ego-depleted participants to take longer to see a reversal disappears when they are informed of the ambiguity, they still make fewer reversals overall.

This pattern is consistent with reduced bottom-upwards processing in ego-depleted participants. After ego depletion, it takes longer to reverse when uninformed of ambiguity (bottom-upwardly), which disappears when informed (top-downwards). The addition of this top-downward data greatly increases the number of reversals seen, but has much the aforementioned result on both control and ego-depleted participants, suggesting both are every bit sensitive to height-down processing. Ego-depleted participants persist in seeing fewer reversal when informed, consistent with reduced bottom-upward processing.

General give-and-take

The current aim was to examine whether the depletion of inhibitory command reduces the feel of reversal. Adapting an ego depletion epitome from social psychology (Baumeister et al., 1998), inhibitory control was slightly reduced later on ego depletion (Experiment ane), but it is important to stress that the effect is small-scale. In Experiment 2, when ego-depleted adults viewed ambiguous figures, they were less likely to opposite ambiguous figures. Thus, in addition to findings demonstrating that inhibitory control allows or stabilises reversal (e.k., Strüber & Stadler, 1999; Wimmer & Doherty, 2011), the current findings reveal that the depletion of inhibitory resource may reduce reversal. Reversal reduction occurred when both existence naïve and informed of ambiguity, suggesting ego depletion furnishings on both bottom-upwardly and height-downwardly processes.

It is unclear what mechanisms underlie ego depletion, and in that location is debate whether ego depletion reflects the depletion of low-level processes (Baumeister et al., 1998) or reduces agile motivation and attention to reach a goal or perform a task (Inzlicht et al., 2014). The electric current findings cannot directly reply this debate, and the reduction in reversal rate when informed of ambiguity tin exist a result of both neural fatigue effects (bottom-upwardly) and lack of motivation to focus on the task (top-downwardly). However, the additional finding that ego depletion increased response time to reverse initially when naïve about the ambiguity is in line with the suggestion that ego depletion particularly reduces bottom-up processing (Baumeister et al., 1998) rather than solely affecting superlative-down processing (Inzlicht et al., 2014). Thus, overall, a hybrid model of ego depletion involving both bottom-upwards and elevation-downward processes seems more plausible.

However, the size of the ego depletion effect has recently been put into question in a preregistered replication study involving 23 laboratories (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2016). Event sizes on response time differences between ego-depleted and control participants ranged between Cohen's d = -.06 and .36, with a 95% confidence interval. Moreover, task performance varied greatly in accuracy both between ego-depleted and control participants and across different laboratories (15%–44% of participants performing <80% correct) (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2016). Clearly, this raises the upshot of the forcefulness of the ego depletion effect and how minor procedural differences beyond laboratories, different populations, and variation in task operation affect the overall forcefulness of the upshot (Baumeister & Vohs, 2016). Our single lab findings reveal a small ego depletion event and do not support previous results showing strong effects of ego depletion on inhibitory Stroop functioning (Johns, Inzlicht, & Schmader, 2008). Power analysis (G*Ability; Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) suggests that we had sufficient ability (174 participants needed) to observe large sized effects at d = .five. In Experiment 2, the ego depletion outcome was larger, demonstrating novel furnishings in visual perception. Thus, the current enquiry supports demonstrations of the effect across a wide domain of tasks (Hagger et al., 2010), only raises the question of the size of the effect.

Furthermore, findings from the ego depletion literature are at odds with the traditional cognitive literature on sequential modulation effects. When a task poses response conflict, then inhibitory control performance is enhanced in a second self-control task due to activated cerebral control or priming (Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001; Mayr, Awh, & Laurey, 2003). Specifically, responding to an incongruent Flanker task trial reduces response fourth dimension on an immediately followed incongruent number Stroop trial when participants are initially aware of trial difficulty (Fernandez-Duque & Knight, 2008). Crucially, the sequential modulation effect occurs on a trial-by-trial basis when task type varies across trials as opposed to the sequential job paradigm in ego depletion. Thus, when the cognitive system is put under response conflict across unlike tasks, it can enhance cognitive command beyond tasks online on a trial-by-trial basis (cognitive literature on sequential modulation), only not when the task menses is interrupted (ego depletion literature). This departure between online task date and task intermission may cause participants to testify opposite self-command effects. Hereafter enquiry might desire to straight investigate this merits.

Overall, current findings provide novel insights into the functional dependence of inhibitory processes on the disambiguation of visual information under naïve and informed conditions. The depletion of inhibitory control may reduce our visual perceptual feel of reversal.

References

-

Alós-Ferrer, C., Hügelschäfer, S., & Li, J. (2015). Self-command depletion and decision making. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, viii, 203–216. doi:x.1037/npe0000047

-

Baumeister, R. F. (2014). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and inhibition. Neuropsychologia, 65, 313–319. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.08.012

-

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, K., & Tice, D. Chiliad. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252–1265. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.five.1252

-

Bialystok, E., & Shapero, D. (2005). Ambiguous benefits: The effect of bilingualism on reversing ambiguous figures. Developmental Science, 8, 595–604. doi:10.1111/j.14677687.2005.00451.x

-

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. Southward., Barch, D. Grand., Carter, C. Southward., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Disharmonize monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108, 624–652. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.624

-

Botwinick, J. (1961). Husband and father-in-law: A reversible figure. American Journal of Psychology, 74, 312–113.

-

Bugelski, B. R., & Alampay, D. A. (1961). The role of frequency in developing perceptual sets. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 15, 205–211. doi:10.1037/h0083443

-

Carlson, Due south. M., & Meltzoff, A. M. (2008). Bilingual experience and executive performance in young children. Developmental Science, 11, 282–298. doi:ten.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x

-

Damian, M. F., & Freeman, Due north. H. (2008). Flexible and inflexible response components: A Stroop study with typewritten output. Acta Psychologica, 128, 91–101. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.10.002

-

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-K., & Buchner, A. (2007). K*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis plan for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146

-

Fernandez-Duque, D., & Knight, M. B. (2008). Cerebral control: Dynamic, sustained, and voluntary influences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Functioning, 34, 340–355. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.34.ii.340

-

Fisher, G. (1967). Measuring ambiguity. American Journal of Psychology, 80, 541–557. doi:10.2307/1421187

-

Galliot, M. T., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. North., Maner, J. K., Plant, E. A., Tice, D. M., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2007). Self-control relies on glucose as a limited free energy source: Willpower is more than than a metaphor. Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 325–336. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325

-

Hagger, Thou. S., Forest, C., Stiff, C., & Chatzisarantis, Northward. L. D. (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 495–525. doi:10.1037/a0019486

-

Hochberg, J., & Peterson, K. A. (1987). Piecemeal organization and cerebral components in object perception: Perceptually coupled responses to moving objects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Full general, 116, 370–380. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.116.4.370

-

Inzlicht, M., Schmeichel, B. J., & Mcrae, N. C. (2014). Why self-command seems (but may not be) limited. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, eighteen, 127–133. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.009

-

Jastrow, J. (1900). Fact and fable in psychology. Oxford: Houghton Mifflin.

-

Johns, M., Inzlicht, One thousand., & Schmader, T. (2008). Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: Examining the influence of emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Full general, 137, 691–705. doi:10.1037/a0013834

-

Logan, Thou. D., & Zbrodoff, J. N. (1998). Stroop-type interference: Congruity effects in color naming with typewritten responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Homo Perception and Performance, 24, 978–992. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.24.3.978

-

Long, G. 1000., & Batterman, J. M. (2012). Dissecting perceptual processes with a new tri-stable reversible effigy. Perception, 41, 1163–1185. doi:10.1068/p7313

-

Long, G. One thousand., & Toppino, T. C. (2004). Enduring involvement in perceptual ambiguity: Alternating views of reversible figures. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 748–768. doi:ten.1037/0033-2909.130.5.748

-

Ludwig, C., Borella, E., Tettamanti, 1000., & de Ribaupierre, A. (2010). Adult historic period differences in the color Stroop test: A comparison betwixt an item-by-item and blocked version. Archives of Gerontology and Elderliness, 51, 135–142. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2009.09.040

-

Mathes, B., Strüber, D., Stadler, Thou. A., & Basar-Eroglu, C. (2006). Voluntary control of Necker cube reversals modulates the EEG delta- and gamma-ring response. Neuroscience Messages, 402, 145–149. doi:x.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.063

-

Mayr, U., Awh, E., & Laurey, P. (2003). Conflict adaptation effects in the absence of executive control. Nature Neuroscience, 6, 450–452. doi:ten.1038/nn1051

-

Melcher, D., & Wade, N. J. (2006). Cavern art interpretation II. Perception, 35, 719–722. doi:10.1068/p3506ed

-

Meng, 1000., & Tong, F. (2004). Tin can attention selectively bias bistable perception? Differences betwixt binocular rivalry and ambiguous figures. Journal of Vision, four, 539–551. doi:x.1167/iv.vii.two

-

Muraven, K., & Slessareva, Eastward. (2003). Mechanisms of cocky-control failure: Motivation and limited resource. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 894–906. doi:10.1177/0146167203029007008

-

Peterson, One thousand. A., & Gibson, B. S. (1991). Directing spatial attention within an object: Altering the functional equivalence of shape descriptions. Periodical of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Operation, 17, 170–182. doi:x.1037/0096-1523.17.one.170

-

Salo, R., Henik, A., & Robertson, Fifty. C. (2001). Interpreting Stroop interference: An analysis of differences between task versions. Neuropsychology, 15, 462–471. doi:10.1037/08944105.15.4.462

-

Slotnik, S. D., & Yantis, Due south. (2005). Common neural substrates for the control and effects of visual attention and perceptual bistability. Cognitive Brain Research, 24, 97–108. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.12.008

-

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Periodical of Experimental Psychology, eighteen, 643–662. doi:10.1037/h0054651

-

Strüber, D., & Stadler, One thousand. (1999). Differences in peak-downwards influences on the reversal rate of dissimilar categories of reversible figures. Perception, 28, 1185–1196. doi:ten.1068/p2973

-

Suzuki, South., & Peterson, M. A. (2000). Multiplicative effects of intention on the perception of bistable apparent movement. Psychological Science, 11, 202–209. doi:x.1111/1467-9280.00242

-

Van Ee, R., van Dam, Fifty. C. J., & Brouwer, G. J. (2005). Voluntary control and the dynamics of perceptual bi-stability. Vision Enquiry, 45, 41–55. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2004.07.030

-

Ward, East. J., & Scholl, B. J. (2015). Inattentional blindness reflects limitations on perception, not retentiveness: Testify from repeated failures of awareness. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 722–727. doi:x.3758/s13423-014-0745-8

-

Wimmer, One thousand. C., & Doherty, 1000. J. (2011). The development of ambiguous figure perception. Monographs of the Society for Enquiry in Child Development, 76(1), 1–130.

-

Wimmer, Thousand. C., & Marx, C. (2014). Inhibitory processes in visual perception: A bilingual advantage. Journal of Experimental Kid Psychology, 126, 412–419.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Rights and permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Wimmer, G.C., Stirk, S. & Hancock, P.J.B. Ego depletion in visual perception: Ego-depleted viewers feel less ambiguous figure reversal. Psychon Bull Rev 24, 1620–1626 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1247-two

-

Published:

-

Event Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.3758/s13423-017-1247-ii

Keywords

- Cryptic figures

- Reversal

- Lesser-upwardly processes

- Superlative-down processes

- Ego depletion

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-017-1247-2

0 Response to "Visual Perception Art Do You See a Rabbit Blojob"

Post a Comment